first published in The Dragon Chronicle,

Number 12, April 1998-

The Draco Constellation

In a recent issue of The Dragon Chronicle we discussed the Romanian Sky Myth

(McBeath & Gheorghe 1997), and saw the central role the Dragon

played in creating the Milky Way.

In Romania, as across the modern western world, this dragon

was portrayed in the constellations as Draco.

Here, we present a short review of the old Romanian interpretations of

the other sky dragon and celestial serpent star-patterns, except Hydrus, which

were the subject of an earlier Dragon Chronicle series (McBeath 1996a, b, 1997).

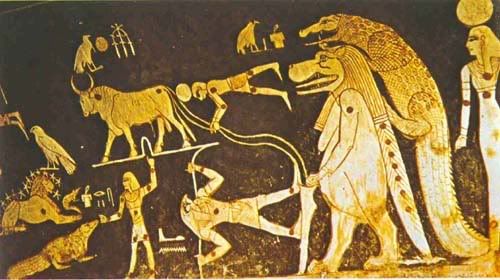

The funeral camera of Seti I in Luxor.

Two of these constellations have been identified with the modern ones: The ox (that are the Great Bear),

the circumpolar in Egypt, and the Crocodile and Hipopótamo (Dragoon and the Little Bear).

Surprisingly, Cetus and Hydra do not figure at all prominently in

Romanian sky lore, although Serpens and Ophiuchus combined appears as

one giant constellation, Sarpele, the Serpent. Ion Ottescu (1907) suggested that

the Romanian peasants were primarily interested in stars and constellations as

a means of timing during the most important part of the agricultural year,

chiefly the period between June to September,most notably July-August.

They looked at the risings of certain stars and constellations,

and their positions at midnight and dawn, and used those as

signposts for their work in the fields.

Neither Cetus nor Hydra are easy to see at such a time.

As Ottescu puts it, “Only the shepherds are interested in the rest of the year”!

Cetus has a slight advantage over Hydra,

modernly rising completely before dawn by the July-August boundary.

In the past, its rising time would have been somewhat more favourable,

as the position on the ecliptic where the Sun lies at midsummer was east of where

it now lies, in Gemini or Cancer between 2000 to 3000 years ago, for instance.

The solstice point is now reached near the Taurus-Gemini border.

As a result, Cetus is the better-known of the pair, and is called Chitul, the Whale,

perceived as the great fish that swallowed the prophet Jonah for three days

(cf. Wansbrough 1994, pp.1541-1542; Jonah 2:1-11).

However, this enormous sea creature links back to Tiamat, as one of the creatures

of the deep, and a symbol of the Sea itself, conquered by the god Yahweh

(e.g. Wansbrough 1994, p.765, note f).

Yahweh here, in a sense, echoes Marduk’s defeat of Tiamat,

from the earlier Mesopotamian myth (cf. Dalley 1989, pp.228-277),

and the fish becomes Yahweh’s tool, much as Marduk’s symbol in

Mesopotamian iconography was the mushussu dragon.

The most prominent part of Hydra, the “head to heart” section,

still modernly lies not far from the summer solstice point.

As a consequence, this part of Hydra is invisible to northern hemisphere sites

for much of the summer today.

In the past, the problem was still more severe, and was at its worst around

3000 years ago, when the summer solstice occurred in the constellation of Cancer,

directly over the head of Hydra. Presumably because of this,

Hydra has only two partial representatives in Romanian tales.

Firstly, she appears as a zmeoaica, a many-headed dragon-woman,

who had poisonous breath, making her quite similar to the Greek hydra.

In some respects, she is perhaps closer to a cross between the Greek hydra

and the gorgon Medusa.

Her second incarnation is as Gheonoaia, a giant bird-woman,

who could unleash a wind by flapping her wings that could fell the trees.

Gheonoaia has a sister called Scorpia, a flying serpent-woman able to

pour out fire and burning pitch from her mouth.

Both the zmeoaica and Gheonoaia (and Scorpia too) are enemies that

the major Romanian hero Fat Frumos, “Beautiful Boy”,

has to overcome in separate myths.

Fat Frumos is a hero figure who is equated with the constellation of The Man,

Omul, in Romanian sky lore.

He is also similar to the Greek Herakles - who appears in the sky as Hercules,

the same constellation that Fat Frumos is associated with.

When we look at Serpens/Sarpele the Serpent, we find a much more complex

symbol in the Romanian myths.

As a star-pattern, it is much larger than the western Serpens,

as it includes Ophiuchus, and forms a large coil shape in the sky,

with its head just under Corona Borealis (where we find Serpens’ head too).

This region of sky lies almost opposite the summer solstice point, and as a

consequence, is visible almost all night during the summer - and was even

2000-3000 years ago - which accounts for its greater prominence

in Romanian sky lore.

With the overlain Christian symbolism found in many of the

Romanian constellations, this Serpent becomes the snake that tempted Eve

at the garden in Eden (Genesis 3:1-15; e.g. Wansbrough 1994, p.20).

A later Romanian belief translated Sarpele into the Road of Lost Men, i.e.

where sinners stray, afraid of the Second Coming of the Christian Messiah

and his Judgement.

There are several curious points about this.

On a physical level, the region of Ophiuchus-Serpens leads away westwards

from the brighter regions of the Milky Way, and so can literally be interpreted as

a “path” of stars leading off into the “darkness” away from the Milky Way.

The Milky Way itself is frequently perceived as an important, often royal,

road in the sky, sometimes one which dead souls must traverse after leaving

the Earth (cf. Allen 1963, pp.474-485; Olcott 1911, pp.391-398).

The Milky Way occasionally features mythically as a huge serpent as well,

but we will not pursue this point further here.

The constellation representing Eve’s tempting snake is frequently thought of

as Draco, although there is often confusion in trying to discover which of

the sky’s dragons may have been meant by the various biblical allusions

to such creatures (see for instance the discussion in Allen 1963, pp.202-203).

It is quite possible either Serpens/Sarpele or Draco would serve equally well.

As a coiling serpent, Sarpele might perhaps better be seen as the “crooked serpent”

found in the King James’ translation of the Bible (Job 25:13), although

more accurate modern translations suggest this should be “Fleeing Serpent”

(e.g. Wansbrough 1994, p.785).

As the Serpent in the Romanian Sky Myth was banished by the use of Hora,

the Ring Dance (see McBeath & Gheorghe 1997), the idea that

the “Fleeing Serpent” could be Sarpele/Serpens is certainly an interesting one.

Such an active term is distinctly more appropriate to the rapid motion of a

constellation across the southern sky during the night, than the apparently

very sluggish rotation of Draco near the celestial pole.

Wansbrough (1994; p.759, notes d and e) also indicates that this Serpent

was Leviathan, for which he additionally gives the term Dragon as synonymous.

He describes Leviathan as “a monster of primeval chaos” and further suggests

that this was the creature that swallowed the Sun in eclipses.

Again, we come back to Tiamat and the dragon.

Symbolically, we find two principal representations in the Romanian tales.

The first, and most important, is as a cunning, malevolent character (not

dissimilar to some of trickster/controller figures found in mythologies worldwide).

Tudor Pamfile’s folklore quotation in (Kernbach 1983) amends the

biblical temptation of Eve: “‘Listen to me, Eve’, said the Snake. ‘Adam thinks

we have fallen in love, and wants to separate us.’”; is one example.

Another comes from the ballad “The Snake” (collected by T. Balasel

from Oltenia in southern Romania).

Here, a mother curses her son to be “of the Snake”, because of the pains

he tortured her with at his birth.

When the boy grows up to be a young man, a great snake born the same day

as him appears, and swallows half of him.

Fortunately, the brave hero Dobrisan awakes in time to discover what is happening,

cuts open the snake, rescues the boy and purifies him by washing him in milk.

This echoes the biblical tale again, in that Eve’s punishment for being tempted

by the snake was to always suffer intense agonies in childbirth

(Genesis 3:16; e.g. Wansbrough 1994, p.20).

Milk as an anti-venom substance was discussed earlier in

(McBeath & Gheorghe 1997).

The second Romanian snake symbol concerns a small,

non-venomous type called Sarpele Casei, the “House Snake”.

Tudor Pamfile in (Kernsbach 1983) notes: “When the [house] snake flees

from a house, that house will remain unlived-in”, as a traditional Romanian belief.

There is a lower-level hint here of a belief similar to that in which if the ravens

leave the Tower of London, then England will cease to exist.

This belief seems to derive ultimately from the Celtic deity Bran the Blessed,

whose sacred bird was the raven, and whose head was thought to be buried in a hill,

perhaps Tower Hill, near London, protecting England from her enemies.

Something of this deity and his exploits can also be found in Romanian myths,

but that is another story.

………………………………………………….

ASTROPOETICAL FANTASY

-astropoem by Andrei Dorian Gheorghe-

“In the Romanian tradition, he who is pricked by a venomous monster

can be purified by milk.”

Cetus, Hydra and Serpens

Made a monstrous coalition

To destroy the Milky Way,

But every time the noble stars

Drive them away.

Then the Milky Way

Purifies the sky

From their poison,

Giving us fortunate mornings.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Two interesting links related to Draco Constellation and the ancient cult of the serpent in Pre-Tracia, Mesopotamia and Egypt:

D R A C O - Mythology and history

Origins of snake worship

No comments:

Post a Comment