Thursday, February 11, 2010

Saturday, January 23, 2010

DARKNESS

"The waves were dead; the tides were in their grave,

The moon, their mistress, had expir'd before;

The winds were wither'd in the stagnant air,

And the clouds perish'd; Darkness had no need

Of aid from them -- She was the Universe."

I don`t know the author.

The moon, their mistress, had expir'd before;

The winds were wither'd in the stagnant air,

And the clouds perish'd; Darkness had no need

Of aid from them -- She was the Universe."

I don`t know the author.

TZADIKIM NISTARIM

Also called the Lamed Vev, two letters in the Hebrew alphabet that translate to the number thirty-six. In this violent, ugly, strife-riddled world of ours there are thirty-six men, the Hidden Just Men or Hidden Saints, who bear on their shoulders the burden of all our pain, sorrows and sins. The Tzadikim Nistarim move in obscurity, and are usually found among the poor, the downtrodden and the meekest among us, and are chosen for this task because of their righteousness, stalwart sense of genuine justice, and the true goodness of their souls. When one of these men dies, God chooses another to take his place. It is for their sake and for love of them that God does not destroy His imperfect creation. As long as the Lamed Vav serves humanity, the world will continue to plod on, but once one of them dies and God cannot find another worthy to take his place, the world will be destroyed. In Qabala, the thirty-six men of the Tzadikim Nistarim together combine to symbolize the seventy-two bridges, corresponding to the seventy-two names of God, that connect the concealed and revealed worlds of our universe.

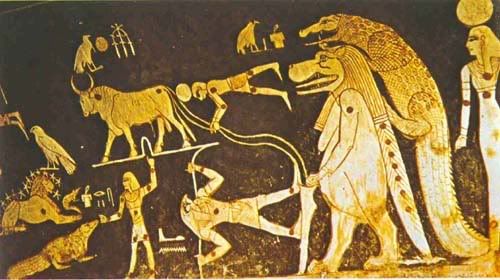

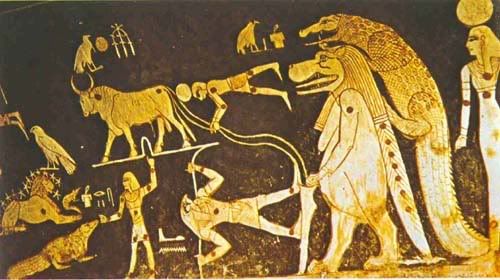

Dragon symbolism

Symbolism from Carl G. Jung's Mysterium Coniunctions: Dragon is personification of Sulphur and is by far the male element. Since the dragon is said to impregnate himself by swallowing his tail, then the tail is the male organ and the mouth is the female organ. The dragon consumes its entire body into his head; thus, partaking of his most dangerous and evil nature turning it into the inner fire of Mercury. This evil dragon nature which sulphur shares is frequently called the "dragon's head" (caput dragonis), which is a "most pernicious poison," a poisonous vapor breathed out by the flying dragon. However,the "winged dragon" that stands for quicksilver becomes a poison-breathing monster only after it unites with the "wingless dragon" which corresponds to sulphur. In psychological terms these two dragons represent the opposites; the winged dragon tries to prevent the wingless dragon from flying. They are always in confrontation until the wingless dragon flies, symbolizing the conquering of an obstacle, or obstacles, preventing total individualization. In other words, the winged dragon represents personal obstacles that must be overcome to insure a more-perfect being; thus, leading to the saying: "You conquer the dragon or he will conquer you."

Romanian Mythology - Iele

In Romanian mythology, the Iele are feminine mythical creatures.

Clear characteristic are hard to be attributed. Most of the times they are described as virgin fairies (zane in Romanian), with great seduction power over men, with magic skills, attributes similar to the Ancient Greek Nymphs, Naiads, Dryads, etc. The Iele live in the sky, in the forests, in caves, on isolated mountain cliffs, in marshes, often bathing in the springs, or at crossroads. From this point of view, the Iele are similar with the Ancient Greek Hecate, a three headed goddess of Thracian origin, which guards the crossroads. They mostly appear at night, under the moonlight, as dancing Horas, in seclusive areas like glades, the tops of certain trees (maples, walnut trees), ponds, river sides, crossroads or abandoned fireplaces, dancing naked, with their breast almost covered by their disheveled hair, with bells to their ankles, and carrying candles. In almost all of these instances, the Iele appear acorporal. Rarely, they are dressed in chain mail coats. The effect of their specific dance, the Hora, has similar characteristics with the dances of the Bacchants. The place where they had danced would after remain carbonized, with the grass incapable of growing on the trodden ground, and with the leafs of the surrounding trees scorched. Later, when grass would finally grow, it would have a red or dark-green color, the animals would not eat it, but instead mushrooms would thrive on it. The Iele don’t live a solitary life. They gather in groups in the air, they can fly with or without wings; they can travel with incredible speeds, either on their own, or with chariots made of fire.

The Iele appear sometimes with bodies, other times only as immaterial spirits. They are young and beautiful, voluptuous, immortals, their frenzy causing delirium to the watchers, with bad tempers, but not being necessarily evil. They come in a group of unknown numbers, either in a group of seven, and sometimes in groups of three. This version is mostly found in Oltenia, were these three Iele are considered the daughters of Alexander the Great, and are called Catrina, Zalina and Marina.

They are not generally considered evil genies: they resort to revenge only when they are provoked, offended, seen while they dance, when people step on the trodden ground left behind by their dance, sleep under a tree which the Iele consider as their property, drink from the springs or wells used by them. Terrible punishes are inflicted upon the ones who refuse their invitation to dance, or the ones who mimic their movements. The one who randomly hears their songs, becomes instantly mute. A main characteristic is their beautiful voices which are used to spell their listeners, just like the Mermaids from ancient Greek mythology. Invisible to humans, there are however certain moments when they can be seen by mortals, like during night, when they dance. When this happens, they abduct the victim, punishing the “guilty” one with magical spells, after they previously caused him to fall into sleep with the sounds and the vertigo of the frenetic Hora, which they dance around their victim. The ones abducted, and which had the unfortunate inspiration to learn the songs of the Iele, disappear forever without a trace.

The Iele are also believed to be agents of revenge, of God or of the Devil, having the right to avenge in the name of their “employers. When they were called upon to act, they hounded their victims into the middle of their dance, until they died in a furor of madness or torment. In this hypostasis, the Iele are similar to the Ancient Greek Erinyes and the Roman Furies.

Dimitrie Cantemir describes the Iele as ‘’Nymphs of the air, inloved especially with young men’’. The origin of these beliefs is unknown. The name iele, is the Romanian popular word for "them" (feminine). Their real names are secret and inaccessible, and are commonly replaced with symbols based on their characteristics. There names based on epithets are: Iele, Dânse, Drăgaice, Vilve, Iezme, Izme, Irodiţe, Rusalii, Nagode, Vântoase, Domniţe, Măiestre, Frumoase, Muşate, Fetele Codrului, Împărătesele Văzduhului, Zânioare, Sfinte de noapte, Şoimane, Mândre, Fecioare, Albe, Hale, etc. But there are also personal names which appear: Ana, Bugiana, Dumernica, Foiofia, Lacargia, Magdalina, Ruxanda, Tiranda, Trandafira, Rudeana, Ruja, Trandafira, Pascuta, Cosânzeana, Orgisceana, Lemnica, Rosia, Todosia, Sandalina, Ruxanda, Margalina, Savatina, Rujalina, etc. These names must not be used randomly, as they may be the base for dangerous enchantments. It is believed that every witch knows nine of these pseudonyms, from which she makes combinations, and who are the bases for spells.

To please the Iele, the people had dedicated to them festival days: the Rusaliile, the Stratul, the Sfredelul or Bulciul Rusaliilor, the nine days after the Easter, the Marina, the Foca, etc. Whoever doesn’t respect these holidays, will suffer the revenge of the Iele: men and women who work during these days would be lifted in spinning vertigos, people and cattle would suffer mysterious deaths or become paralyzed and crippled, hail would fall, flooding would happen, the trees would wither, the houses would catch fire.

But the people also invented cures against the Iele, either preventive: garlic and mugwort wore around the waist, in their bosom, or hanged to their hats, the hanging the skull of a horse in a pole in front of the house, either exorcistic customs. In this category, the most important cure is the dance of Căluşari. This customs was the subject of episode of the popular TV series, The X-Files (see The X-Files (season 2))

The same common Indo-European mythology base is also suggested by the close resemblance with the Nordic Elves, youthful feminine humanoid spirits of great beauty living in forests and other natural places, underground, or in wells and springs, having as sacred tree the same maple tree, and with magical powers, having the ability to cast spells with their circle dances. The elves too leave a kind of circle were they had danced the älvdanser (elf dances) or älvringar (elf circles). Typically, this circle also consisted of a ring of small mushrooms. Arguably, Iele are the Romanian equivalent of the fays of other cultures, like of the nymphs of Greek and Roman mythology, of the vili from Slavic mythology, and of the Irish sídhe.

Clear characteristic are hard to be attributed. Most of the times they are described as virgin fairies (zane in Romanian), with great seduction power over men, with magic skills, attributes similar to the Ancient Greek Nymphs, Naiads, Dryads, etc. The Iele live in the sky, in the forests, in caves, on isolated mountain cliffs, in marshes, often bathing in the springs, or at crossroads. From this point of view, the Iele are similar with the Ancient Greek Hecate, a three headed goddess of Thracian origin, which guards the crossroads. They mostly appear at night, under the moonlight, as dancing Horas, in seclusive areas like glades, the tops of certain trees (maples, walnut trees), ponds, river sides, crossroads or abandoned fireplaces, dancing naked, with their breast almost covered by their disheveled hair, with bells to their ankles, and carrying candles. In almost all of these instances, the Iele appear acorporal. Rarely, they are dressed in chain mail coats. The effect of their specific dance, the Hora, has similar characteristics with the dances of the Bacchants. The place where they had danced would after remain carbonized, with the grass incapable of growing on the trodden ground, and with the leafs of the surrounding trees scorched. Later, when grass would finally grow, it would have a red or dark-green color, the animals would not eat it, but instead mushrooms would thrive on it. The Iele don’t live a solitary life. They gather in groups in the air, they can fly with or without wings; they can travel with incredible speeds, either on their own, or with chariots made of fire.

The Iele appear sometimes with bodies, other times only as immaterial spirits. They are young and beautiful, voluptuous, immortals, their frenzy causing delirium to the watchers, with bad tempers, but not being necessarily evil. They come in a group of unknown numbers, either in a group of seven, and sometimes in groups of three. This version is mostly found in Oltenia, were these three Iele are considered the daughters of Alexander the Great, and are called Catrina, Zalina and Marina.

They are not generally considered evil genies: they resort to revenge only when they are provoked, offended, seen while they dance, when people step on the trodden ground left behind by their dance, sleep under a tree which the Iele consider as their property, drink from the springs or wells used by them. Terrible punishes are inflicted upon the ones who refuse their invitation to dance, or the ones who mimic their movements. The one who randomly hears their songs, becomes instantly mute. A main characteristic is their beautiful voices which are used to spell their listeners, just like the Mermaids from ancient Greek mythology. Invisible to humans, there are however certain moments when they can be seen by mortals, like during night, when they dance. When this happens, they abduct the victim, punishing the “guilty” one with magical spells, after they previously caused him to fall into sleep with the sounds and the vertigo of the frenetic Hora, which they dance around their victim. The ones abducted, and which had the unfortunate inspiration to learn the songs of the Iele, disappear forever without a trace.

The Iele are also believed to be agents of revenge, of God or of the Devil, having the right to avenge in the name of their “employers. When they were called upon to act, they hounded their victims into the middle of their dance, until they died in a furor of madness or torment. In this hypostasis, the Iele are similar to the Ancient Greek Erinyes and the Roman Furies.

Dimitrie Cantemir describes the Iele as ‘’Nymphs of the air, inloved especially with young men’’. The origin of these beliefs is unknown. The name iele, is the Romanian popular word for "them" (feminine). Their real names are secret and inaccessible, and are commonly replaced with symbols based on their characteristics. There names based on epithets are: Iele, Dânse, Drăgaice, Vilve, Iezme, Izme, Irodiţe, Rusalii, Nagode, Vântoase, Domniţe, Măiestre, Frumoase, Muşate, Fetele Codrului, Împărătesele Văzduhului, Zânioare, Sfinte de noapte, Şoimane, Mândre, Fecioare, Albe, Hale, etc. But there are also personal names which appear: Ana, Bugiana, Dumernica, Foiofia, Lacargia, Magdalina, Ruxanda, Tiranda, Trandafira, Rudeana, Ruja, Trandafira, Pascuta, Cosânzeana, Orgisceana, Lemnica, Rosia, Todosia, Sandalina, Ruxanda, Margalina, Savatina, Rujalina, etc. These names must not be used randomly, as they may be the base for dangerous enchantments. It is believed that every witch knows nine of these pseudonyms, from which she makes combinations, and who are the bases for spells.

To please the Iele, the people had dedicated to them festival days: the Rusaliile, the Stratul, the Sfredelul or Bulciul Rusaliilor, the nine days after the Easter, the Marina, the Foca, etc. Whoever doesn’t respect these holidays, will suffer the revenge of the Iele: men and women who work during these days would be lifted in spinning vertigos, people and cattle would suffer mysterious deaths or become paralyzed and crippled, hail would fall, flooding would happen, the trees would wither, the houses would catch fire.

But the people also invented cures against the Iele, either preventive: garlic and mugwort wore around the waist, in their bosom, or hanged to their hats, the hanging the skull of a horse in a pole in front of the house, either exorcistic customs. In this category, the most important cure is the dance of Căluşari. This customs was the subject of episode of the popular TV series, The X-Files (see The X-Files (season 2))

The same common Indo-European mythology base is also suggested by the close resemblance with the Nordic Elves, youthful feminine humanoid spirits of great beauty living in forests and other natural places, underground, or in wells and springs, having as sacred tree the same maple tree, and with magical powers, having the ability to cast spells with their circle dances. The elves too leave a kind of circle were they had danced the älvdanser (elf dances) or älvringar (elf circles). Typically, this circle also consisted of a ring of small mushrooms. Arguably, Iele are the Romanian equivalent of the fays of other cultures, like of the nymphs of Greek and Roman mythology, of the vili from Slavic mythology, and of the Irish sídhe.

Au bord de la mer

Au sortir de ce bal, nous suivîmes les grèves ;

Vers le toit d'un exil, au hasard du chemin,

Nous allions : une fleur se fanait dans sa main ;

C'était par un minuit d'étoiles et de rêves.

Dans l'ombre, autour de nous, tombaient des flots foncés.

Vers les lointains d'opale et d'or, sur l'Atlantique,

L'outre-mer épandait sa lumière mystique ;

Les algues parfumaient les espaces glacés ;

Les vieux échos sonnaient dans la falaise entière !

Et les nappes de l'onde aux volutes sans frein

Ecumaient, lourdement, contre les rocs d'airain.

Sur la dune brillaient les croix d'un cimetière.

Leur silence, pour nous, couvrait ce vaste bruit.

Elles ne tendaient plus, croix par l'ombre insultées,

Les couronnes de deuil, fleurs de morts emportées

Dans les flots tonnants, par les tempêtes, la nuit.

Mais de ces blancs tombeaux en pente sur la rive,

Sous la brume sacrée à des clartés pareils,

L'ombre questionnait en vain les grands sommeils :

Ils gardaient le secret de la Loi décisive.

Frileuse, elle voilait d'un cachemire noir,

Son sein, royal exil de toutes mes pensées !

J'admirais cette femme aux paupières baissées,

Sphinx cruel, mauvais rêve, ancien désespoir.

Ses regards font mourir les enfants. Elle passe.

Et se laisse survivre en ce qu'elle détruit,

C'est la femme qu'on aime à cause de la Nuit,

Et ceux qui l'ont connue en parlent à voix basse.

Le danger la revêt d'un rayon familier :

Même dans son étreinte oublieusement tendre,

Ses crimes, évoqués, sont tels qu'on croit entendre

Des crosses de fusils tombant sur le palier.

Cependant, sous la honte illustre qui l'enchaîne,

Sous le deuil où se plaît cette âme sans essor,

Repose une candeur inviolée encor

Comme un lys enfermé dans un coffret d'ébène.

Elle prêta l'oreille au tumulte des mers,

Inclina son beau front touché par les années,

Et, se remémorant ses mornes destinées,

Elle se répandit en ces termes amers :

"Autrefois, autrefois - quand je faisais partie

Des vivants, - leurs amours sous les pâles flambeaux

Des nuits, comme la mer au pied de ces tombeaux,

Se lamentaient, houleux, devant mon apathie.

J'ai vu de longs adieux sur mes mains se briser ;

Mortelle, j'accueillais, sans désir et sans haine,

Les aveux suppliants de ces âmes en peine :

Le sépulcre à la mer ne rend pas son baiser.

Je suis donc insensible et faite de silence

Et je n'ai pas vécu ; mes jours sont froids et vains ;

Les Cieux m'ont refusé les battements divins !

On a faussé pour moi les poids de la balance.

Je sens que c'est mon sort même dans le trépas :

Et, soucieux encor des regrets ou des fêtes,

Si les morts vont chercher leurs fleurs dans les tempêtes,

Moi je reposerai, ne les comprenant pas."

Je saluai les croix lumineuses et pâles.

L'étendue annonçait l'aurore, et je me pris

A dire, pour calmer ses ténébreux esprits

Que le vent du remords battait de ses rafales

Et pendant que la mer déserte se gonflait :

"Au bal vous n'aviez pas ces mélancolies

Et les sons de cristal de vos phrases polies

Charmaient le serpent d'or de votre bracelet.

Rieuse et respirant une touffe de roses

Sous vos grands cheveux noirs mêlés de diamants,

Quand la valse nous prit, tous deux, quelques moments,

Vous eûtes, en vos yeux, des lueurs moins moroses ?

J'étais heureux de voir sous le plaisir vermeil

Se ranimer votre âme à l'oubli toute prête,

Et s'éclairer enfin votre douleur distraite,

Comme un glacier frappé d'un rayon de soleil."

Elle laissa briller sur moi ses yeux funèbres,

Et la pâleur des morts ornait ses traits fatals.

"Selon vous, je ressemble aux pays boréals,

J'ai six mois de clarté et six mois de ténèbres ?

Sache mieux quel orgueil nous nous sommes donné !

Et tout ce qu'en nos yeux il empêche de lire...

Aime-moi toi qui sais que, sous un clair sourire,

Je suis pareille à ces tombeaux abandonnés."

Auguste Villiers de L'Isle-Adam, Conte d'Amour.

Vers le toit d'un exil, au hasard du chemin,

Nous allions : une fleur se fanait dans sa main ;

C'était par un minuit d'étoiles et de rêves.

Dans l'ombre, autour de nous, tombaient des flots foncés.

Vers les lointains d'opale et d'or, sur l'Atlantique,

L'outre-mer épandait sa lumière mystique ;

Les algues parfumaient les espaces glacés ;

Les vieux échos sonnaient dans la falaise entière !

Et les nappes de l'onde aux volutes sans frein

Ecumaient, lourdement, contre les rocs d'airain.

Sur la dune brillaient les croix d'un cimetière.

Leur silence, pour nous, couvrait ce vaste bruit.

Elles ne tendaient plus, croix par l'ombre insultées,

Les couronnes de deuil, fleurs de morts emportées

Dans les flots tonnants, par les tempêtes, la nuit.

Mais de ces blancs tombeaux en pente sur la rive,

Sous la brume sacrée à des clartés pareils,

L'ombre questionnait en vain les grands sommeils :

Ils gardaient le secret de la Loi décisive.

Frileuse, elle voilait d'un cachemire noir,

Son sein, royal exil de toutes mes pensées !

J'admirais cette femme aux paupières baissées,

Sphinx cruel, mauvais rêve, ancien désespoir.

Ses regards font mourir les enfants. Elle passe.

Et se laisse survivre en ce qu'elle détruit,

C'est la femme qu'on aime à cause de la Nuit,

Et ceux qui l'ont connue en parlent à voix basse.

Le danger la revêt d'un rayon familier :

Même dans son étreinte oublieusement tendre,

Ses crimes, évoqués, sont tels qu'on croit entendre

Des crosses de fusils tombant sur le palier.

Cependant, sous la honte illustre qui l'enchaîne,

Sous le deuil où se plaît cette âme sans essor,

Repose une candeur inviolée encor

Comme un lys enfermé dans un coffret d'ébène.

Elle prêta l'oreille au tumulte des mers,

Inclina son beau front touché par les années,

Et, se remémorant ses mornes destinées,

Elle se répandit en ces termes amers :

"Autrefois, autrefois - quand je faisais partie

Des vivants, - leurs amours sous les pâles flambeaux

Des nuits, comme la mer au pied de ces tombeaux,

Se lamentaient, houleux, devant mon apathie.

J'ai vu de longs adieux sur mes mains se briser ;

Mortelle, j'accueillais, sans désir et sans haine,

Les aveux suppliants de ces âmes en peine :

Le sépulcre à la mer ne rend pas son baiser.

Je suis donc insensible et faite de silence

Et je n'ai pas vécu ; mes jours sont froids et vains ;

Les Cieux m'ont refusé les battements divins !

On a faussé pour moi les poids de la balance.

Je sens que c'est mon sort même dans le trépas :

Et, soucieux encor des regrets ou des fêtes,

Si les morts vont chercher leurs fleurs dans les tempêtes,

Moi je reposerai, ne les comprenant pas."

Je saluai les croix lumineuses et pâles.

L'étendue annonçait l'aurore, et je me pris

A dire, pour calmer ses ténébreux esprits

Que le vent du remords battait de ses rafales

Et pendant que la mer déserte se gonflait :

"Au bal vous n'aviez pas ces mélancolies

Et les sons de cristal de vos phrases polies

Charmaient le serpent d'or de votre bracelet.

Rieuse et respirant une touffe de roses

Sous vos grands cheveux noirs mêlés de diamants,

Quand la valse nous prit, tous deux, quelques moments,

Vous eûtes, en vos yeux, des lueurs moins moroses ?

J'étais heureux de voir sous le plaisir vermeil

Se ranimer votre âme à l'oubli toute prête,

Et s'éclairer enfin votre douleur distraite,

Comme un glacier frappé d'un rayon de soleil."

Elle laissa briller sur moi ses yeux funèbres,

Et la pâleur des morts ornait ses traits fatals.

"Selon vous, je ressemble aux pays boréals,

J'ai six mois de clarté et six mois de ténèbres ?

Sache mieux quel orgueil nous nous sommes donné !

Et tout ce qu'en nos yeux il empêche de lire...

Aime-moi toi qui sais que, sous un clair sourire,

Je suis pareille à ces tombeaux abandonnés."

Auguste Villiers de L'Isle-Adam, Conte d'Amour.

Le cri

"Je longeais le chemin avec deux amis - c'est alors que le soleil se coucha - le ciel devint tout à coup rouge couleur de sang - je m'arrêtai, m'adossai contre une barrière - le fjord d'un noir bleuté et la ville était inondés de sang et ravagés par des langues de feu - mes amis poursuivirent leur chemin, tandis que je tremblais encore d'angoisse - et je sentis que la nature était traversée par un long cri infini."

Edvard Munch, 1892.

Le cri

Edvard Munch, 1892.

Le cri

Lamia

by John Keats

1819

"I had not a dispute but a disquisition with Dilke, on various subjects; several things dovetailed in my mind, & at once it struck me, what quality went to form a Man of Achievement especially in literature & which Shakespeare possessed so enormously - I mean Negative Capability, that is when man is capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts without any irritable reaching after fact & reason."

Keats believed that great people (especially poets) have the ability to accept that not everything can be resolved. Keats was a Romantic and believed that the truths found in the imagination access holy authority. Such authority cannot otherwise be understood, and thus he writes of "uncertainties." This "being in uncertaint[y]" is a place between the mundane, ready reality and the multiple potentials of a more fully understood existence.

Part I

Upon a time, before the faery broods

Drove Nymph and Satyr from the prosperous woods,

Before King Oberon's bright diadem,

Sceptre, and mantle, clasp'd with dewy gem,

Frighted away the Dryads and the Fauns

From rushes green, and brakes, and cowslip'd lawns,

The ever-smitten Hermes empty left

His golden throne, bent warm on amorous theft:

From high Olympus had he stolen light,

On this side of Jove's clouds, to escape the sight

Of his great summoner, and made retreat

Into a forest on the shores of Crete.

For somewhere in that sacred island dwelt

A nymph, to whom all hoofed Satyrs knelt;

At whose white feet the languid Tritons poured

Pearls, while on land they wither'd and adored.

Fast by the springs where she to bathe was wont,

And in those meads where sometime she might haunt,

Were strewn rich gifts, unknown to any Muse,

Though Fancy's casket were unlock'd to choose.

Ah, what a world of love was at her feet!

So Hermes thought, and a celestial heat

Burnt from his winged heels to either ear,

That from a whiteness, as the lily clear,

Blush'd into roses 'mid his golden hair,

Fallen in jealous curls about his shoulders bare.

From vale to vale, from wood to wood, he flew,

Breathing upon the flowers his passion new,

And wound with many a river to its head,

To find where this sweet nymph prepar'd her secret bed:

In vain; the sweet nymph might nowhere be found,

And so he rested, on the lonely ground,

Pensive, and full of painful jealousies

Of the Wood-Gods, and even the very trees.

There as he stood, he heard a mournful voice,

Such as once heard, in gentle heart, destroys

All pain but pity: thus the lone voice spake:

"When from this wreathed tomb shall I awake!

When move in a sweet body fit for life,

And love, and pleasure, and the ruddy strife

Of hearts and lips! Ah, miserable me!"

The God, dove-footed, glided silently

Round bush and tree, soft-brushing, in his speed,

The taller grasses and full-flowering weed,

Until he found a palpitating snake,

Bright, and cirque-couchant in a dusky brake.

She was a gordian shape of dazzling hue,

Vermilion-spotted, golden, green, and blue;

Striped like a zebra, freckled like a pard,

Eyed like a peacock, and all crimson barr'd;

And full of silver moons, that, as she breathed,

Dissolv'd, or brighter shone, or interwreathed

Their lustres with the gloomier tapestries -

So rainbow-sided, touch'd with miseries,

She seem'd, at once, some penanced lady elf,

Some demon's mistress, or the demon's self.

Upon her crest she wore a wannish fire

Sprinkled with stars, like Ariadne's tiar:

Her head was serpent, but ah, bitter-sweet!

She had a woman's mouth with all its pearls complete:

And for her eyes: what could such eyes do there

But weep, and weep, that they were born so fair?

As Proserpine still weeps for her Sicilian air.

Her throat was serpent, but the words she spake

Came, as through bubbling honey, for Love's sake,

And thus; while Hermes on his pinions lay,

Like a stoop'd falcon ere he takes his prey.

"Fair Hermes, crown'd with feathers, fluttering light,

I had a splendid dream of thee last night:

I saw thee sitting, on a throne of gold,

Among the Gods, upon Olympus old,

The only sad one; for thou didst not hear

The soft, lute-finger'd Muses chaunting clear,

Nor even Apollo when he sang alone,

Deaf to his throbbing throat's long, long melodious moan.

I dreamt I saw thee, robed in purple flakes,

Break amorous through the clouds, as morning breaks,

And, swiftly as a bright Phoebean dart,

Strike for the Cretan isle; and here thou art!

Too gentle Hermes, hast thou found the maid?"

Whereat the star of Lethe not delay'd

His rosy eloquence, and thus inquired:

"Thou smooth-lipp'd serpent, surely high inspired!

Thou beauteous wreath, with melancholy eyes,

Possess whatever bliss thou canst devise,

Telling me only where my nymph is fled, -

Where she doth breathe!" "Bright planet, thou hast said,"

Return'd the snake, "but seal with oaths, fair God!"

"I swear," said Hermes, "by my serpent rod,

And by thine eyes, and by thy starry crown!"

Light flew his earnest words, among the blossoms blown.

Then thus again the brilliance feminine:

"Too frail of heart! for this lost nymph of thine,

Free as the air, invisibly, she strays

About these thornless wilds; her pleasant days

She tastes unseen; unseen her nimble feet

Leave traces in the grass and flowers sweet;

From weary tendrils, and bow'd branches green,

She plucks the fruit unseen, she bathes unseen:

And by my power is her beauty veil'd

To keep it unaffronted, unassail'd

By the love-glances of unlovely eyes,

Of Satyrs, Fauns, and blear'd Silenus' sighs.

Pale grew her immortality, for woe

Of all these lovers, and she grieved so

I took compassion on her, bade her steep

Her hair in weird syrops, that would keep

Her loveliness invisible, yet free

To wander as she loves, in liberty.

Thou shalt behold her, Hermes, thou alone,

If thou wilt, as thou swearest, grant my boon!"

Then, once again, the charmed God began

An oath, and through the serpent's ears it ran

Warm, tremulous, devout, psalterian.

Ravish'd, she lifted her Circean head,

Blush'd a live damask, and swift-lisping said,

"I was a woman, let me have once more

A woman's shape, and charming as before.

I love a youth of Corinth - O the bliss!

Give me my woman's form, and place me where he is.

Stoop, Hermes, let me breathe upon thy brow,

And thou shalt see thy sweet nymph even now."

The God on half-shut feathers sank serene,

She breath'd upon his eyes, and swift was seen

Of both the guarded nymph near-smiling on the green.

It was no dream; or say a dream it was,

Real are the dreams of Gods, and smoothly pass

Their pleasures in a long immortal dream.

One warm, flush'd moment, hovering, it might seem

Dash'd by the wood-nymph's beauty, so he burn'd;

Then, lighting on the printless verdure, turn'd

To the swoon'd serpent, and with languid arm,

Delicate, put to proof the lythe Caducean charm.

So done, upon the nymph his eyes he bent,

Full of adoring tears and blandishment,

And towards her stept: she, like a moon in wane,

Faded before him, cower'd, nor could restrain

Her fearful sobs, self-folding like a flower

That faints into itself at evening hour:

But the God fostering her chilled hand,

She felt the warmth, her eyelids open'd bland,

And, like new flowers at morning song of bees,

Bloom'd, and gave up her honey to the lees.

Into the green-recessed woods they flew;

Nor grew they pale, as mortal lovers do.

Left to herself, the serpent now began

To change; her elfin blood in madness ran,

Her mouth foam'd, and the grass, therewith besprent,

Wither'd at dew so sweet and virulent;

Her eyes in torture fix'd, and anguish drear,

Hot, glaz'd, and wide, with lid-lashes all sear,

Flash'd phosphor and sharp sparks, without one cooling tear.

The colours all inflam'd throughout her train,

She writh'd about, convuls'd with scarlet pain:

A deep volcanian yellow took the place

Of all her milder-mooned body's grace;

And, as the lava ravishes the mead,

Spoilt all her silver mail, and golden brede;

Made gloom of all her frecklings, streaks and bars,

Eclips'd her crescents, and lick'd up her stars:

So that, in moments few, she was undrest

Of all her sapphires, greens, and amethyst,

And rubious-argent: of all these bereft,

Nothing but pain and ugliness were left.

Still shone her crown; that vanish'd, also she

Melted and disappear'd as suddenly;

And in the air, her new voice luting soft,

Cried, "Lycius! gentle Lycius!" - Borne aloft

With the bright mists about the mountains hoar

These words dissolv'd: Crete's forests heard no more.

Whither fled Lamia, now a lady bright,

A full-born beauty new and exquisite?

She fled into that valley they pass o'er

Who go to Corinth from Cenchreas' shore;

And rested at the foot of those wild hills,

The rugged founts of the Peraean rills,

And of that other ridge whose barren back

Stretches, with all its mist and cloudy rack,

South-westward to Cleone. There she stood

About a young bird's flutter from a wood,

Fair, on a sloping green of mossy tread,

By a clear pool, wherein she passioned

To see herself escap'd from so sore ills,

While her robes flaunted with the daffodils.

Ah, happy Lycius! - for she was a maid

More beautiful than ever twisted braid,

Or sigh'd, or blush'd, or on spring-flowered lea

Spread a green kirtle to the minstrelsy:

A virgin purest lipp'd, yet in the lore

Of love deep learned to the red heart's core:

Not one hour old, yet of sciential brain

To unperplex bliss from its neighbour pain;

Define their pettish limits, and estrange

Their points of contact, and swift counterchange;

Intrigue with the specious chaos, and dispart

Its most ambiguous atoms with sure art;

As though in Cupid's college she had spent

Sweet days a lovely graduate, still unshent,

And kept his rosy terms in idle languishment.

Why this fair creature chose so fairily

By the wayside to linger, we shall see;

But first 'tis fit to tell how she could muse

And dream, when in the serpent prison-house,

Of all she list, strange or magnificent:

How, ever, where she will'd, her spirit went;

Whether to faint Elysium, or where

Down through tress-lifting waves the Nereids fair

Wind into Thetis' bower by many a pearly stair;

Or where God Bacchus drains his cups divine,

Stretch'd out, at ease, beneath a glutinous pine;

Or where in Pluto's gardens palatine

Mulciber's columns gleam in far piazzian line.

And sometimes into cities she would send

Her dream, with feast and rioting to blend;

And once, while among mortals dreaming thus,

She saw the young Corinthian Lycius

Charioting foremost in the envious race,

Like a young Jove with calm uneager face,

And fell into a swooning love of him.

Now on the moth-time of that evening dim

He would return that way, as well she knew,

To Corinth from the shore; for freshly blew

The eastern soft wind, and his galley now

Grated the quaystones with her brazen prow

In port Cenchreas, from Egina isle

Fresh anchor'd; whither he had been awhile

To sacrifice to Jove, whose temple there

Waits with high marble doors for blood and incense rare.

Jove heard his vows, and better'd his desire;

For by some freakful chance he made retire

From his companions, and set forth to walk,

Perhaps grown wearied of their Corinth talk:

Over the solitary hills he fared,

Thoughtless at first, but ere eve's star appeared

His phantasy was lost, where reason fades,

In the calm'd twilight of Platonic shades.

Lamia beheld him coming, near, more near -

Close to her passing, in indifference drear,

His silent sandals swept the mossy green;

So neighbour'd to him, and yet so unseen

She stood: he pass'd, shut up in mysteries,

His mind wrapp'd like his mantle, while her eyes

Follow'd his steps, and her neck regal white

Turn'd - syllabling thus, "Ah, Lycius bright,

And will you leave me on the hills alone?

Lycius, look back! and be some pity shown."

He did; not with cold wonder fearingly,

But Orpheus-like at an Eurydice;

For so delicious were the words she sung,

It seem'd he had lov'd them a whole summer long:

And soon his eyes had drunk her beauty up,

Leaving no drop in the bewildering cup,

And still the cup was full, - while he afraid

Lest she should vanish ere his lip had paid

Due adoration, thus began to adore;

Her soft look growing coy, she saw his chain so sure:

"Leave thee alone! Look back! Ah, Goddess, see

Whether my eyes can ever turn from thee!

For pity do not this sad heart belie -

Even as thou vanishest so I shall die.

Stay! though a Naiad of the rivers, stay!

To thy far wishes will thy streams obey:

Stay! though the greenest woods be thy domain,

Alone they can drink up the morning rain:

Though a descended Pleiad, will not one

Of thine harmonious sisters keep in tune

Thy spheres, and as thy silver proxy shine?

So sweetly to these ravish'd ears of mine

Came thy sweet greeting, that if thou shouldst fade

Thy memory will waste me to a shade -

For pity do not melt!" - "If I should stay,"

Said Lamia, "here, upon this floor of clay,

And pain my steps upon these flowers too rough,

What canst thou say or do of charm enough

To dull the nice remembrance of my home?

Thou canst not ask me with thee here to roam

Over these hills and vales, where no joy is, -

Empty of immortality and bliss!

Thou art a scholar, Lycius, and must know

That finer spirits cannot breathe below

In human climes, and live: Alas! poor youth,

What taste of purer air hast thou to soothe

My essence? What serener palaces,

Where I may all my many senses please,

And by mysterious sleights a hundred thirsts appease?

It cannot be - Adieu!" So said, she rose

Tiptoe with white arms spread. He, sick to lose

The amorous promise of her lone complain,

Swoon'd, murmuring of love, and pale with pain.

The cruel lady, without any show

Of sorrow for her tender favourite's woe,

But rather, if her eyes could brighter be,

With brighter eyes and slow amenity,

Put her new lips to his, and gave afresh

The life she had so tangled in her mesh:

And as he from one trance was wakening

Into another, she began to sing,

Happy in beauty, life, and love, and every thing,

A song of love, too sweet for earthly lyres,

While, like held breath, the stars drew in their panting fires

And then she whisper'd in such trembling tone,

As those who, safe together met alone

For the first time through many anguish'd days,

Use other speech than looks; bidding him raise

His drooping head, and clear his soul of doubt,

For that she was a woman, and without

Any more subtle fluid in her veins

Than throbbing blood, and that the self-same pains

Inhabited her frail-strung heart as his.

And next she wonder'd how his eyes could miss

Her face so long in Corinth, where, she said,

She dwelt but half retir'd, and there had led

Days happy as the gold coin could invent

Without the aid of love; yet in content

Till she saw him, as once she pass'd him by,

Where 'gainst a column he leant thoughtfully

At Venus' temple porch, 'mid baskets heap'd

Of amorous herbs and flowers, newly reap'd

Late on that eve, as 'twas the night before

The Adonian feast; whereof she saw no more,

But wept alone those days, for why should she adore?

Lycius from death awoke into amaze,

To see her still, and singing so sweet lays;

Then from amaze into delight he fell

To hear her whisper woman's lore so well;

And every word she spake entic'd him on

To unperplex'd delight and pleasure known.

Let the mad poets say whate'er they please

Of the sweets of Fairies, Peris, Goddesses,

There is not such a treat among them all,

Haunters of cavern, lake, and waterfall,

As a real woman, lineal indeed

From Pyrrha's pebbles or old Adam's seed.

Thus gentle Lamia judg'd, and judg'd aright,

That Lycius could not love in half a fright,

So threw the goddess off, and won his heart

More pleasantly by playing woman's part,

With no more awe than what her beauty gave,

That, while it smote, still guaranteed to save.

Lycius to all made eloquent reply,

Marrying to every word a twinborn sigh;

And last, pointing to Corinth, ask'd her sweet,

If 'twas too far that night for her soft feet.

The way was short, for Lamia's eagerness

Made, by a spell, the triple league decrease

To a few paces; not at all surmised

By blinded Lycius, so in her comprized.

They pass'd the city gates, he knew not how

So noiseless, and he never thought to know.

As men talk in a dream, so Corinth all,

Throughout her palaces imperial,

And all her populous streets and temples lewd,

Mutter'd, like tempest in the distance brew'd,

To the wide-spreaded night above her towers.

Men, women, rich and poor, in the cool hours,

Shuffled their sandals o'er the pavement white,

Companion'd or alone; while many a light

Flared, here and there, from wealthy festivals,

And threw their moving shadows on the walls,

Or found them cluster'd in the corniced shade

Of some arch'd temple door, or dusky colonnade.

Muffling his face, of greeting friends in fear,

Her fingers he press'd hard, as one came near

With curl'd gray beard, sharp eyes, and smooth bald crown,

Slow-stepp'd, and robed in philosophic gown:

Lycius shrank closer, as they met and past,

Into his mantle, adding wings to haste,

While hurried Lamia trembled: "Ah," said he,

"Why do you shudder, love, so ruefully?

Why does your tender palm dissolve in dew?" -

"I'm wearied," said fair Lamia: "tell me who

Is that old man? I cannot bring to mind

His features - Lycius! wherefore did you blind

Yourself from his quick eyes?" Lycius replied,

'Tis Apollonius sage, my trusty guide

And good instructor; but to-night he seems

The ghost of folly haunting my sweet dreams.

While yet he spake they had arrived before

A pillar'd porch, with lofty portal door,

Where hung a silver lamp, whose phosphor glow

Reflected in the slabbed steps below,

Mild as a star in water; for so new,

And so unsullied was the marble hue,

So through the crystal polish, liquid fine,

Ran the dark veins, that none but feet divine

Could e'er have touch'd there. Sounds Aeolian

Breath'd from the hinges, as the ample span

Of the wide doors disclos'd a place unknown

Some time to any, but those two alone,

And a few Persian mutes, who that same year

Were seen about the markets: none knew where

They could inhabit; the most curious

Were foil'd, who watch'd to trace them to their house:

And but the flitter-winged verse must tell,

For truth's sake, what woe afterwards befel,

'Twould humour many a heart to leave them thus,

Shut from the busy world of more incredulous.

Part II

love in a hut, with water and a crust,

Is - Love, forgive us! - cinders, ashes, dust;

Love in a palace is perhaps at last

More grievous torment than a hermit's fast -

That is a doubtful tale from faery land,

Hard for the non-elect to understand.

Had Lycius liv'd to hand his story down,

He might have given the moral a fresh frown,

Or clench'd it quite: but too short was their bliss

To breed distrust and hate, that make the soft voice hiss.

Besides, there, nightly, with terrific glare,

Love, jealous grown of so complete a pair,

Hover'd and buzz'd his wings, with fearful roar,

Above the lintel of their chamber door,

And down the passage cast a glow upon the floor.

For all this came a ruin: side by side

They were enthroned, in the even tide,

Upon a couch, near to a curtaining

Whose airy texture, from a golden string,

Floated into the room, and let appear

Unveil'd the summer heaven, blue and clear,

Betwixt two marble shafts: - there they reposed,

Where use had made it sweet, with eyelids closed,

Saving a tythe which love still open kept,

That they might see each other while they almost slept;

When from the slope side of a suburb hill,

Deafening the swallow's twitter, came a thrill

Of trumpets - Lycius started - the sounds fled,

But left a thought, a buzzing in his head.

For the first time, since first he harbour'd in

That purple-lined palace of sweet sin,

His spirit pass'd beyond its golden bourn

Into the noisy world almost forsworn.

The lady, ever watchful, penetrant,

Saw this with pain, so arguing a want

Of something more, more than her empery

Of joys; and she began to moan and sigh

Because he mused beyond her, knowing well

That but a moment's thought is passion's passing bell.

"Why do you sigh, fair creature?" whisper'd he:

"Why do you think?" return'd she tenderly:

"You have deserted me - where am I now?

Not in your heart while care weighs on your brow:

No, no, you have dismiss'd me; and I go

From your breast houseless: ay, it must be so."

He answer'd, bending to her open eyes,

Where he was mirror'd small in paradise,

My silver planet, both of eve and morn!

Why will you plead yourself so sad forlorn,

While I am striving how to fill my heart

With deeper crimson, and a double smart?

How to entangle, trammel up and snare

Your soul in mine, and labyrinth you there

Like the hid scent in an unbudded rose?

Ay, a sweet kiss - you see your mighty woes.

My thoughts! shall I unveil them? Listen then!

What mortal hath a prize, that other men

May be confounded and abash'd withal,

But lets it sometimes pace abroad majestical,

And triumph, as in thee I should rejoice

Amid the hoarse alarm of Corinth's voice.

Let my foes choke, and my friends shout afar,

While through the thronged streets your bridal car

Wheels round its dazzling spokes." The lady's cheek

Trembled; she nothing said, but, pale and meek,

Arose and knelt before him, wept a rain

Of sorrows at his words; at last with pain

Beseeching him, the while his hand she wrung,

To change his purpose. He thereat was stung,

Perverse, with stronger fancy to reclaim

Her wild and timid nature to his aim:

Besides, for all his love, in self despite,

Against his better self, he took delight

Luxurious in her sorrows, soft and new.

His passion, cruel grown, took on a hue

Fierce and sanguineous as 'twas possible

In one whose brow had no dark veins to swell.

Fine was the mitigated fury, like

Apollo's presence when in act to strike

The serpent - Ha, the serpent! certes, she

Was none. She burnt, she lov'd the tyranny,

And, all subdued, consented to the hour

When to the bridal he should lead his paramour.

Whispering in midnight silence, said the youth,

"Sure some sweet name thou hast, though, by my truth,

I have not ask'd it, ever thinking thee

Not mortal, but of heavenly progeny,

As still I do. Hast any mortal name,

Fit appellation for this dazzling frame?

Or friends or kinsfolk on the citied earth,

To share our marriage feast and nuptial mirth?"

"I have no friends," said Lamia," no, not one;

My presence in wide Corinth hardly known:

My parents' bones are in their dusty urns

Sepulchred, where no kindled incense burns,

Seeing all their luckless race are dead, save me,

And I neglect the holy rite for thee.

Even as you list invite your many guests;

But if, as now it seems, your vision rests

With any pleasure on me, do not bid

Old Apollonius - from him keep me hid."

Lycius, perplex'd at words so blind and blank,

Made close inquiry; from whose touch she shrank,

Feigning a sleep; and he to the dull shade

Of deep sleep in a moment was betray'd

It was the custom then to bring away

The bride from home at blushing shut of day,

Veil'd, in a chariot, heralded along

By strewn flowers, torches, and a marriage song,

With other pageants: but this fair unknown

Had not a friend. So being left alone,

(Lycius was gone to summon all his kin)

And knowing surely she could never win

His foolish heart from its mad pompousness,

She set herself, high-thoughted, how to dress

The misery in fit magnificence.

She did so, but 'tis doubtful how and whence

Came, and who were her subtle servitors.

About the halls, and to and from the doors,

There was a noise of wings, till in short space

The glowing banquet-room shone with wide-arched grace.

A haunting music, sole perhaps and lone

Supportress of the faery-roof, made moan

Throughout, as fearful the whole charm might fade.

Fresh carved cedar, mimicking a glade

Of palm and plantain, met from either side,

High in the midst, in honour of the bride:

Two palms and then two plantains, and so on,

From either side their stems branch'd one to one

All down the aisled place; and beneath all

There ran a stream of lamps straight on from wall to wall.

So canopied, lay an untasted feast

Teeming with odours. Lamia, regal drest,

Silently paced about, and as she went,

In pale contented sort of discontent,

Mission'd her viewless servants to enrich

The fretted splendour of each nook and niche.

Between the tree-stems, marbled plain at first,

Came jasper pannels; then, anon, there burst

Forth creeping imagery of slighter trees,

And with the larger wove in small intricacies.

Approving all, she faded at self-will,

And shut the chamber up, close, hush'd and still,

Complete and ready for the revels rude,

When dreadful guests would come to spoil her solitude.

The day appear'd, and all the gossip rout.

O senseless Lycius! Madman! wherefore flout

The silent-blessing fate, warm cloister'd hours,

And show to common eyes these secret bowers?

The herd approach'd; each guest, with busy brain,

Arriving at the portal, gaz'd amain,

And enter'd marveling: for they knew the street,

Remember'd it from childhood all complete

Without a gap, yet ne'er before had seen

That royal porch, that high-built fair demesne;

So in they hurried all, maz'd, curious and keen:

Save one, who look'd thereon with eye severe,

And with calm-planted steps walk'd in austere;

'Twas Apollonius: something too he laugh'd,

As though some knotty problem, that had daft

His patient thought, had now begun to thaw,

And solve and melt - 'twas just as he foresaw.

He met within the murmurous vestibule

His young disciple. "'Tis no common rule,

Lycius," said he, "for uninvited guest

To force himself upon you, and infest

With an unbidden presence the bright throng

Of younger friends; yet must I do this wrong,

And you forgive me." Lycius blush'd, and led

The old man through the inner doors broad-spread;

With reconciling words and courteous mien

Turning into sweet milk the sophist's spleen.

Of wealthy lustre was the banquet-room,

Fill'd with pervading brilliance and perfume:

Before each lucid pannel fuming stood

A censer fed with myrrh and spiced wood,

Each by a sacred tripod held aloft,

Whose slender feet wide-swerv'd upon the soft

Wool-woofed carpets: fifty wreaths of smoke

From fifty censers their light voyage took

To the high roof, still mimick'd as they rose

Along the mirror'd walls by twin-clouds odorous.

Twelve sphered tables, by silk seats insphered,

High as the level of a man's breast rear'd

On libbard's paws, upheld the heavy gold

Of cups and goblets, and the store thrice told

Of Ceres' horn, and, in huge vessels, wine

Come from the gloomy tun with merry shine.

Thus loaded with a feast the tables stood,

Each shrining in the midst the image of a God.

When in an antichamber every guest

Had felt the cold full sponge to pleasure press'd,

By minist'ring slaves, upon his hands and feet,

And fragrant oils with ceremony meet

Pour'd on his hair, they all mov'd to the feast

In white robes, and themselves in order placed

Around the silken couches, wondering

Whence all this mighty cost and blaze of wealth could spring.

Soft went the music the soft air along,

While fluent Greek a vowel'd undersong

Kept up among the guests discoursing low

At first, for scarcely was the wine at flow;

But when the happy vintage touch'd their brains,

Louder they talk, and louder come the strains

Of powerful instruments - the gorgeous dyes,

The space, the splendour of the draperies,

The roof of awful richness, nectarous cheer,

Beautiful slaves, and Lamia's self, appear,

Now, when the wine has done its rosy deed,

And every soul from human trammels freed,

No more so strange; for merry wine, sweet wine,

Will make Elysian shades not too fair, too divine.

Soon was God Bacchus at meridian height;

Flush'd were their cheeks, and bright eyes double bright:

Garlands of every green, and every scent

From vales deflower'd, or forest-trees branch rent,

In baskets of bright osier'd gold were brought

High as the handles heap'd, to suit the thought

Of every guest; that each, as he did please,

Might fancy-fit his brows, silk-pillow'd at his ease.

What wreath for Lamia? What for Lycius?

What for the sage, old Apollonius?

Upon her aching forehead be there hung

The leaves of willow and of adder's tongue;

And for the youth, quick, let us strip for him

The thyrsus, that his watching eyes may swim

Into forgetfulness; and, for the sage,

Let spear-grass and the spiteful thistle wage

War on his temples. Do not all charms fly

At the mere touch of cold philosophy?

There was an awful rainbow once in heaven:

We know her woof, her texture; she is given

In the dull catalogue of common things.

Philosophy will clip an Angel's wings,

Conquer all mysteries by rule and line,

Empty the haunted air, and gnomed mine -

Unweave a rainbow, as it erewhile made

The tender-person'd Lamia melt into a shade.

By her glad Lycius sitting, in chief place,

Scarce saw in all the room another face,

Till, checking his love trance, a cup he took

Full brimm'd, and opposite sent forth a look

'Cross the broad table, to beseech a glance

From his old teacher's wrinkled countenance,

And pledge him. The bald-head philosopher

Had fix'd his eye, without a twinkle or stir

Full on the alarmed beauty of the bride,

Brow-beating her fair form, and troubling her sweet pride.

Lycius then press'd her hand, with devout touch,

As pale it lay upon the rosy couch:

'Twas icy, and the cold ran through his veins;

Then sudden it grew hot, and all the pains

Of an unnatural heat shot to his heart.

"Lamia, what means this? Wherefore dost thou start?

Know'st thou that man?" Poor Lamia answer'd not.

He gaz'd into her eyes, and not a jot

Own'd they the lovelorn piteous appeal:

More, more he gaz'd: his human senses reel:

Some hungry spell that loveliness absorbs;

There was no recognition in those orbs.

"Lamia!" he cried - and no soft-toned reply.

The many heard, and the loud revelry

Grew hush; the stately music no more breathes;

The myrtle sicken'd in a thousand wreaths.

By faint degrees, voice, lute, and pleasure ceased;

A deadly silence step by step increased,

Until it seem'd a horrid presence there,

And not a man but felt the terror in his hair.

"Lamia!" he shriek'd; and nothing but the shriek

With its sad echo did the silence break.

"Begone, foul dream!" he cried, gazing again

In the bride's face, where now no azure vein

Wander'd on fair-spaced temples; no soft bloom

Misted the cheek; no passion to illume

The deep-recessed vision - all was blight;

Lamia, no longer fair, there sat a deadly white.

"Shut, shut those juggling eyes, thou ruthless man!

Turn them aside, wretch! or the righteous ban

Of all the Gods, whose dreadful images

Here represent their shadowy presences,

May pierce them on the sudden with the thorn

Of painful blindness; leaving thee forlorn,

In trembling dotage to the feeblest fright

Of conscience, for their long offended might,

For all thine impious proud-heart sophistries,

Unlawful magic, and enticing lies.

Corinthians! look upon that gray-beard wretch!

Mark how, possess'd, his lashless eyelids stretch

Around his demon eyes! Corinthians, see!

My sweet bride withers at their potency."

"Fool!" said the sophist, in an under-tone

Gruff with contempt; which a death-nighing moan

From Lycius answer'd, as heart-struck and lost,

He sank supine beside the aching ghost.

"Fool! Fool!" repeated he, while his eyes still

Relented not, nor mov'd; "from every ill

Of life have I preserv'd thee to this day,

And shall I see thee made a serpent's prey?"

Then Lamia breath'd death breath; the sophist's eye,

Like a sharp spear, went through her utterly,

Keen, cruel, perceant, stinging: she, as well

As her weak hand could any meaning tell,

Motion'd him to be silent; vainly so,

He look'd and look'd again a level - No!

"A Serpent!" echoed he; no sooner said,

Than with a frightful scream she vanished:

And Lycius' arms were empty of delight,

As were his limbs of life, from that same night.

On the high couch he lay! - his friends came round

Supported him - no pulse, or breath they found,

And, in its marriage robe, the heavy body wound.

by John Keats

1819

"I had not a dispute but a disquisition with Dilke, on various subjects; several things dovetailed in my mind, & at once it struck me, what quality went to form a Man of Achievement especially in literature & which Shakespeare possessed so enormously - I mean Negative Capability, that is when man is capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts without any irritable reaching after fact & reason."

Keats believed that great people (especially poets) have the ability to accept that not everything can be resolved. Keats was a Romantic and believed that the truths found in the imagination access holy authority. Such authority cannot otherwise be understood, and thus he writes of "uncertainties." This "being in uncertaint[y]" is a place between the mundane, ready reality and the multiple potentials of a more fully understood existence.

Part I

Upon a time, before the faery broods

Drove Nymph and Satyr from the prosperous woods,

Before King Oberon's bright diadem,

Sceptre, and mantle, clasp'd with dewy gem,

Frighted away the Dryads and the Fauns

From rushes green, and brakes, and cowslip'd lawns,

The ever-smitten Hermes empty left

His golden throne, bent warm on amorous theft:

From high Olympus had he stolen light,

On this side of Jove's clouds, to escape the sight

Of his great summoner, and made retreat

Into a forest on the shores of Crete.

For somewhere in that sacred island dwelt

A nymph, to whom all hoofed Satyrs knelt;

At whose white feet the languid Tritons poured

Pearls, while on land they wither'd and adored.

Fast by the springs where she to bathe was wont,

And in those meads where sometime she might haunt,

Were strewn rich gifts, unknown to any Muse,

Though Fancy's casket were unlock'd to choose.

Ah, what a world of love was at her feet!

So Hermes thought, and a celestial heat

Burnt from his winged heels to either ear,

That from a whiteness, as the lily clear,

Blush'd into roses 'mid his golden hair,

Fallen in jealous curls about his shoulders bare.

From vale to vale, from wood to wood, he flew,

Breathing upon the flowers his passion new,

And wound with many a river to its head,

To find where this sweet nymph prepar'd her secret bed:

In vain; the sweet nymph might nowhere be found,

And so he rested, on the lonely ground,

Pensive, and full of painful jealousies

Of the Wood-Gods, and even the very trees.

There as he stood, he heard a mournful voice,

Such as once heard, in gentle heart, destroys

All pain but pity: thus the lone voice spake:

"When from this wreathed tomb shall I awake!

When move in a sweet body fit for life,

And love, and pleasure, and the ruddy strife

Of hearts and lips! Ah, miserable me!"

The God, dove-footed, glided silently

Round bush and tree, soft-brushing, in his speed,

The taller grasses and full-flowering weed,

Until he found a palpitating snake,

Bright, and cirque-couchant in a dusky brake.

She was a gordian shape of dazzling hue,

Vermilion-spotted, golden, green, and blue;

Striped like a zebra, freckled like a pard,

Eyed like a peacock, and all crimson barr'd;

And full of silver moons, that, as she breathed,

Dissolv'd, or brighter shone, or interwreathed

Their lustres with the gloomier tapestries -

So rainbow-sided, touch'd with miseries,

She seem'd, at once, some penanced lady elf,

Some demon's mistress, or the demon's self.

Upon her crest she wore a wannish fire

Sprinkled with stars, like Ariadne's tiar:

Her head was serpent, but ah, bitter-sweet!

She had a woman's mouth with all its pearls complete:

And for her eyes: what could such eyes do there

But weep, and weep, that they were born so fair?

As Proserpine still weeps for her Sicilian air.

Her throat was serpent, but the words she spake

Came, as through bubbling honey, for Love's sake,

And thus; while Hermes on his pinions lay,

Like a stoop'd falcon ere he takes his prey.

"Fair Hermes, crown'd with feathers, fluttering light,

I had a splendid dream of thee last night:

I saw thee sitting, on a throne of gold,

Among the Gods, upon Olympus old,

The only sad one; for thou didst not hear

The soft, lute-finger'd Muses chaunting clear,

Nor even Apollo when he sang alone,

Deaf to his throbbing throat's long, long melodious moan.

I dreamt I saw thee, robed in purple flakes,

Break amorous through the clouds, as morning breaks,

And, swiftly as a bright Phoebean dart,

Strike for the Cretan isle; and here thou art!

Too gentle Hermes, hast thou found the maid?"

Whereat the star of Lethe not delay'd

His rosy eloquence, and thus inquired:

"Thou smooth-lipp'd serpent, surely high inspired!

Thou beauteous wreath, with melancholy eyes,

Possess whatever bliss thou canst devise,

Telling me only where my nymph is fled, -

Where she doth breathe!" "Bright planet, thou hast said,"

Return'd the snake, "but seal with oaths, fair God!"

"I swear," said Hermes, "by my serpent rod,

And by thine eyes, and by thy starry crown!"

Light flew his earnest words, among the blossoms blown.

Then thus again the brilliance feminine:

"Too frail of heart! for this lost nymph of thine,

Free as the air, invisibly, she strays

About these thornless wilds; her pleasant days

She tastes unseen; unseen her nimble feet

Leave traces in the grass and flowers sweet;

From weary tendrils, and bow'd branches green,

She plucks the fruit unseen, she bathes unseen:

And by my power is her beauty veil'd

To keep it unaffronted, unassail'd

By the love-glances of unlovely eyes,

Of Satyrs, Fauns, and blear'd Silenus' sighs.

Pale grew her immortality, for woe

Of all these lovers, and she grieved so

I took compassion on her, bade her steep

Her hair in weird syrops, that would keep

Her loveliness invisible, yet free

To wander as she loves, in liberty.

Thou shalt behold her, Hermes, thou alone,

If thou wilt, as thou swearest, grant my boon!"

Then, once again, the charmed God began

An oath, and through the serpent's ears it ran

Warm, tremulous, devout, psalterian.

Ravish'd, she lifted her Circean head,

Blush'd a live damask, and swift-lisping said,

"I was a woman, let me have once more

A woman's shape, and charming as before.

I love a youth of Corinth - O the bliss!

Give me my woman's form, and place me where he is.

Stoop, Hermes, let me breathe upon thy brow,

And thou shalt see thy sweet nymph even now."

The God on half-shut feathers sank serene,

She breath'd upon his eyes, and swift was seen

Of both the guarded nymph near-smiling on the green.

It was no dream; or say a dream it was,

Real are the dreams of Gods, and smoothly pass

Their pleasures in a long immortal dream.

One warm, flush'd moment, hovering, it might seem

Dash'd by the wood-nymph's beauty, so he burn'd;

Then, lighting on the printless verdure, turn'd

To the swoon'd serpent, and with languid arm,

Delicate, put to proof the lythe Caducean charm.

So done, upon the nymph his eyes he bent,

Full of adoring tears and blandishment,

And towards her stept: she, like a moon in wane,

Faded before him, cower'd, nor could restrain

Her fearful sobs, self-folding like a flower

That faints into itself at evening hour:

But the God fostering her chilled hand,

She felt the warmth, her eyelids open'd bland,

And, like new flowers at morning song of bees,

Bloom'd, and gave up her honey to the lees.

Into the green-recessed woods they flew;

Nor grew they pale, as mortal lovers do.

Left to herself, the serpent now began

To change; her elfin blood in madness ran,

Her mouth foam'd, and the grass, therewith besprent,

Wither'd at dew so sweet and virulent;

Her eyes in torture fix'd, and anguish drear,

Hot, glaz'd, and wide, with lid-lashes all sear,

Flash'd phosphor and sharp sparks, without one cooling tear.

The colours all inflam'd throughout her train,

She writh'd about, convuls'd with scarlet pain:

A deep volcanian yellow took the place

Of all her milder-mooned body's grace;

And, as the lava ravishes the mead,

Spoilt all her silver mail, and golden brede;

Made gloom of all her frecklings, streaks and bars,

Eclips'd her crescents, and lick'd up her stars:

So that, in moments few, she was undrest

Of all her sapphires, greens, and amethyst,

And rubious-argent: of all these bereft,

Nothing but pain and ugliness were left.

Still shone her crown; that vanish'd, also she

Melted and disappear'd as suddenly;

And in the air, her new voice luting soft,

Cried, "Lycius! gentle Lycius!" - Borne aloft

With the bright mists about the mountains hoar

These words dissolv'd: Crete's forests heard no more.

Whither fled Lamia, now a lady bright,

A full-born beauty new and exquisite?

She fled into that valley they pass o'er

Who go to Corinth from Cenchreas' shore;

And rested at the foot of those wild hills,

The rugged founts of the Peraean rills,

And of that other ridge whose barren back

Stretches, with all its mist and cloudy rack,

South-westward to Cleone. There she stood

About a young bird's flutter from a wood,

Fair, on a sloping green of mossy tread,

By a clear pool, wherein she passioned

To see herself escap'd from so sore ills,

While her robes flaunted with the daffodils.

Ah, happy Lycius! - for she was a maid

More beautiful than ever twisted braid,

Or sigh'd, or blush'd, or on spring-flowered lea

Spread a green kirtle to the minstrelsy:

A virgin purest lipp'd, yet in the lore

Of love deep learned to the red heart's core:

Not one hour old, yet of sciential brain

To unperplex bliss from its neighbour pain;

Define their pettish limits, and estrange

Their points of contact, and swift counterchange;

Intrigue with the specious chaos, and dispart

Its most ambiguous atoms with sure art;

As though in Cupid's college she had spent

Sweet days a lovely graduate, still unshent,

And kept his rosy terms in idle languishment.

Why this fair creature chose so fairily

By the wayside to linger, we shall see;

But first 'tis fit to tell how she could muse

And dream, when in the serpent prison-house,

Of all she list, strange or magnificent:

How, ever, where she will'd, her spirit went;

Whether to faint Elysium, or where

Down through tress-lifting waves the Nereids fair

Wind into Thetis' bower by many a pearly stair;

Or where God Bacchus drains his cups divine,

Stretch'd out, at ease, beneath a glutinous pine;

Or where in Pluto's gardens palatine

Mulciber's columns gleam in far piazzian line.

And sometimes into cities she would send

Her dream, with feast and rioting to blend;

And once, while among mortals dreaming thus,

She saw the young Corinthian Lycius

Charioting foremost in the envious race,

Like a young Jove with calm uneager face,

And fell into a swooning love of him.

Now on the moth-time of that evening dim

He would return that way, as well she knew,

To Corinth from the shore; for freshly blew

The eastern soft wind, and his galley now

Grated the quaystones with her brazen prow

In port Cenchreas, from Egina isle

Fresh anchor'd; whither he had been awhile

To sacrifice to Jove, whose temple there

Waits with high marble doors for blood and incense rare.

Jove heard his vows, and better'd his desire;

For by some freakful chance he made retire

From his companions, and set forth to walk,

Perhaps grown wearied of their Corinth talk:

Over the solitary hills he fared,

Thoughtless at first, but ere eve's star appeared

His phantasy was lost, where reason fades,

In the calm'd twilight of Platonic shades.

Lamia beheld him coming, near, more near -

Close to her passing, in indifference drear,

His silent sandals swept the mossy green;

So neighbour'd to him, and yet so unseen

She stood: he pass'd, shut up in mysteries,

His mind wrapp'd like his mantle, while her eyes

Follow'd his steps, and her neck regal white

Turn'd - syllabling thus, "Ah, Lycius bright,

And will you leave me on the hills alone?

Lycius, look back! and be some pity shown."

He did; not with cold wonder fearingly,

But Orpheus-like at an Eurydice;

For so delicious were the words she sung,

It seem'd he had lov'd them a whole summer long:

And soon his eyes had drunk her beauty up,

Leaving no drop in the bewildering cup,

And still the cup was full, - while he afraid

Lest she should vanish ere his lip had paid

Due adoration, thus began to adore;

Her soft look growing coy, she saw his chain so sure:

"Leave thee alone! Look back! Ah, Goddess, see

Whether my eyes can ever turn from thee!

For pity do not this sad heart belie -

Even as thou vanishest so I shall die.

Stay! though a Naiad of the rivers, stay!

To thy far wishes will thy streams obey:

Stay! though the greenest woods be thy domain,

Alone they can drink up the morning rain:

Though a descended Pleiad, will not one

Of thine harmonious sisters keep in tune

Thy spheres, and as thy silver proxy shine?

So sweetly to these ravish'd ears of mine

Came thy sweet greeting, that if thou shouldst fade

Thy memory will waste me to a shade -

For pity do not melt!" - "If I should stay,"

Said Lamia, "here, upon this floor of clay,

And pain my steps upon these flowers too rough,

What canst thou say or do of charm enough

To dull the nice remembrance of my home?

Thou canst not ask me with thee here to roam

Over these hills and vales, where no joy is, -

Empty of immortality and bliss!

Thou art a scholar, Lycius, and must know

That finer spirits cannot breathe below

In human climes, and live: Alas! poor youth,

What taste of purer air hast thou to soothe

My essence? What serener palaces,

Where I may all my many senses please,

And by mysterious sleights a hundred thirsts appease?

It cannot be - Adieu!" So said, she rose

Tiptoe with white arms spread. He, sick to lose

The amorous promise of her lone complain,

Swoon'd, murmuring of love, and pale with pain.

The cruel lady, without any show

Of sorrow for her tender favourite's woe,

But rather, if her eyes could brighter be,

With brighter eyes and slow amenity,

Put her new lips to his, and gave afresh

The life she had so tangled in her mesh:

And as he from one trance was wakening

Into another, she began to sing,

Happy in beauty, life, and love, and every thing,

A song of love, too sweet for earthly lyres,

While, like held breath, the stars drew in their panting fires

And then she whisper'd in such trembling tone,

As those who, safe together met alone

For the first time through many anguish'd days,

Use other speech than looks; bidding him raise

His drooping head, and clear his soul of doubt,

For that she was a woman, and without

Any more subtle fluid in her veins

Than throbbing blood, and that the self-same pains

Inhabited her frail-strung heart as his.

And next she wonder'd how his eyes could miss

Her face so long in Corinth, where, she said,

She dwelt but half retir'd, and there had led

Days happy as the gold coin could invent

Without the aid of love; yet in content

Till she saw him, as once she pass'd him by,

Where 'gainst a column he leant thoughtfully

At Venus' temple porch, 'mid baskets heap'd

Of amorous herbs and flowers, newly reap'd

Late on that eve, as 'twas the night before

The Adonian feast; whereof she saw no more,

But wept alone those days, for why should she adore?

Lycius from death awoke into amaze,

To see her still, and singing so sweet lays;

Then from amaze into delight he fell

To hear her whisper woman's lore so well;

And every word she spake entic'd him on

To unperplex'd delight and pleasure known.

Let the mad poets say whate'er they please

Of the sweets of Fairies, Peris, Goddesses,

There is not such a treat among them all,

Haunters of cavern, lake, and waterfall,

As a real woman, lineal indeed

From Pyrrha's pebbles or old Adam's seed.

Thus gentle Lamia judg'd, and judg'd aright,

That Lycius could not love in half a fright,

So threw the goddess off, and won his heart

More pleasantly by playing woman's part,

With no more awe than what her beauty gave,

That, while it smote, still guaranteed to save.

Lycius to all made eloquent reply,

Marrying to every word a twinborn sigh;

And last, pointing to Corinth, ask'd her sweet,

If 'twas too far that night for her soft feet.

The way was short, for Lamia's eagerness

Made, by a spell, the triple league decrease

To a few paces; not at all surmised

By blinded Lycius, so in her comprized.

They pass'd the city gates, he knew not how

So noiseless, and he never thought to know.

As men talk in a dream, so Corinth all,

Throughout her palaces imperial,

And all her populous streets and temples lewd,

Mutter'd, like tempest in the distance brew'd,

To the wide-spreaded night above her towers.

Men, women, rich and poor, in the cool hours,

Shuffled their sandals o'er the pavement white,

Companion'd or alone; while many a light